IEDM 2017:Intel 10nm vs GF 7nm【SemiWiki】

【暂时先搬来原版的吧,翻译版可能要等一段时间咯…最近写论文比较忙,这篇文章还是能看懂不少的吧。这篇文章大概可以解决不少人的疑问。】

原文地址:https://www.semiwiki.com/forum/content/7191-iedm-2017-intel-versus-globalfoundries-leading-edge.html

作者:Scotten Jones

IEDM 2017 – Intel Versus GLOBALFOUNDRIES at the Leading Edge

As I have discussed in previous blogs, IEDM is one of the premier conferences to learn about the latest developments in semiconductor technology.

On Wednesday December 6th, the Circuit and Device Interaction – Advanced Platform Technologies session was held, and Intel presented their 10nm technology and GLOBALFOUNDRIES (GF) presented their 7nm technology. Despite the different node names, the two processes have similar density. In this article I will combine previous disclosures, interviews and the papers to present a detailed comparison of these two leading edge technologies.

1.0 Processes

1.1 Intel 10nm【Intel 10nm制程特征】

The key characteristics of the process are summarized as follows:

Fins – The fins are patterned with SAQP and have a 34nm pitch, are 7nm wide and 46nm high. This is Intel’s third generation FinFET process. An interesting comment during the talk was that fin height can be optimized by product within an approximately 10nm range. The 46nm height quoted is slightly below the middle of the 10nm range.

Gate – Contacted gate pitch (or Contacted Poly Pitch, CPP as I call it) is 54nm, presumably created with SADP. Dummy gates at cell boundaries are eliminated allowing neighboring cells to be isolated by a single gate width reducing area by 20%. Minimum gate length is 18nm.

Spacers– 2nd generation low-k spacers reduce gate to contact capacitance by 7-8%.

Source/Drain – In-situ doped raised source drains.

Strain – 7th generation strain with in-situ doped raised source/drains and a novel NMOS strain orthogonal to the drain. The novel NMOS strain increases drive current by an additional 5%

Work Function Metals – This is Intel’s fifth generation high-k metal gates (HKMG) (Intel introduced HKMG at 45nm ahead of the rest of the industry). All the threshold voltages for this technology are set by using different work function metals. The base process is 4 work function metals producing 2 threshold voltages, an optional 6 work function metal version provides 3 threshold voltages.

Contacts– The process features cobalt filled contacts reducing contact line resistance by 60% versus tungsten and allows contacts over gate for an additional 10% density gains versus standard contacts over isolation. Contacts over gate are created using self-aligned gate contacts. Gate fill is recessed, a silicon carbide etch stop layers is deposited to prevent the gate contacts from shorting to the diffusion contacts and the contact fill is recessed (3 added steps). The self-aligned gate contacts are in addition to the diffusion contacts that were already self-aligned using a silicon nitride layer that was in the 14nm technology. The contact metal stack also includes a conformal titanium layer to wrap around the raised source/drains and a NiSi layer to lower PMOS contacts resistance. Contact resistance is reduced by 1.5x versus 14nm.

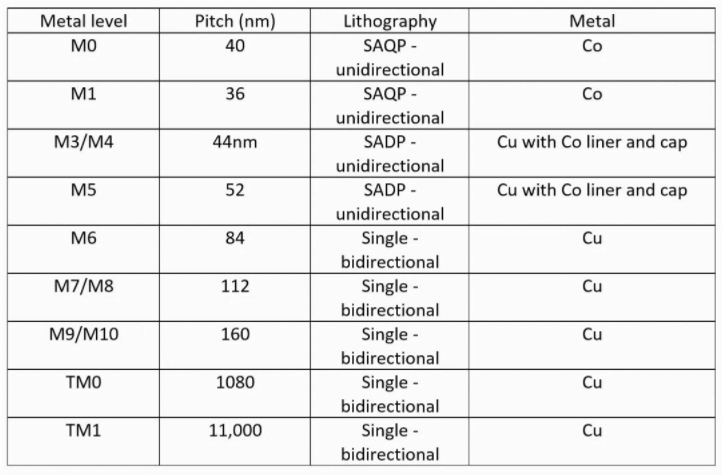

Interconnect Layers – table 1 summarizes the interconnect layers. The process is described in the paper as having 12 interconnect layers but has 13 if you include M0 and both top metals in the table. The interlayer dielectrics are the same as the 14nm technology.

Table 1. Intel Interconnect stack.

SRAM Cell size – High density SRAM cell size of 0.0312um2 and high-performance SRAM cell size is 0.0441um2. 0.56 volt VCC min for low power SRAM.

Logic Cell Size – Minimum Metal Pitch (MMP) is 36nm with a 7.56 track cell for a cell height of 272nm. CPP is 54nm resulting in a cell size of 14,697nm2 (more on this later).

Density – the process offers a 2.7x density increase over 14nm providing what Intel refers to as hyper scaling versus classic 2x density scaling.

Ring oscillator – ring oscillators are 20% faster at the same leakage versus 14nm.

TDDB – improved versus 14nm.

EUV – Intel did not discuss EUV during this talk but did present a paper on EUV at the conference. Intel has 4 EUV tools that they are using for development and they have said they have an optical solution for their 7nm process but will use EUV if it is ready.

1.2 GF 7nm【GF 7nm制程特征】

The key characteristics of the technology are:

Fins – The fins are patterned with SAQP and have a 30nm pitch. This is listed as GF’s third generation FinFET process, GF’s 14nm process was their first generation FinFETs, I am not sure what the second generation was, perhaps an enhanced 14nm version.

Gate – Contacted gate pitch (or Contacted Poly Pitch, CPP as I call it) is 56nm, presumably created with SADP.

Spacers – Not disclosed but I believe it is likely a 2nd generation low-k material such as SiOC.

Source/Drain– raised source/drain epi is also optimized giving a 15% improvement.

Strain – raised source/drains.

Work Function Metals – 2nd generation using multiple work functions to set threshold voltages. GF used multiple work function metals on the 14nm FinFET process they run for IBM (14HP). 8 work function metals are used to provide 4 threshold voltages. All the threshold voltages for this technology are set by using different work function metals.

Contacts – The process features cobalt filled contacts and trench implantation is used to optimize contacts for NMOS and PMOS. Optimization of implants and silicide gives a 39% benefit in contact resistance. Cobalt trench contacts reduce vertical resistance by 40% and when used for local interconnect reduce resistance by 80%.

Interconnect Layers – table 2 summarizes the interconnect layers. The process is described in the paper as having 13 interconnect layers but has 14 if you include M0. The addition of cobalt liners and caps on M0 through M3 improves electromigration by 100x versus 14nm. Without this improvement 7nm power rails would be 3X wider than 14nm but they are actually 4x narrower. By choosing to limit the minimum metal pitch to 40nm SADP could be used. SADP allows wide and narrow metal lines on the same die versus more restrictive SAQP needed for <40nm pitches.

SRAM Cell size– High-density SRAM is 0.0269um2 and high-performance SRAM is 0.0353 um2. Write operations down to 0.5 volts for low power SRAM.

Logic Cell Size– MMP is 40nm with a 6 track cell for a cell height of 240nm. CPP is 56nm resulting in a cell size of 13,440nm2. Larger 9-track cells are also offered for a 10% performance improvement.

Density – the process offers a 2.8x density increase over 14nm and 0.36x scaling for common SOC blocks. GF spent a lot of time optimizing design rules to achieve this.

Cost – Mobile 2 fin 6 track cell provides a >30% costs reduction versus 14nm and depending on the SRAM mix >45% cost reduction.

MIM capacitor – the MIM capacitor offering is 2x the density of the 14nm MIM capacitor.

ASIC – offering available as FX7.

EUV – when EUV is ready a version of this process will be offered with EUV for contacts and vias. By limiting EUV to contacts and vias no shrink is provided but no redesign is required, and 15 masks collapses to 5 masks with a 1.5 day/mask saving in cycle time. One thing I find confusing about this statement is this implies 5 triple patterned optical mask layers becomes 5 single patterned EUV mask layers and yet during the talk 4 color contacts were mentioned. I suppose this could be something like 2 – quadruple patterned contact layers, 1 triple patterned via layer and 2 double patterned via layers. I asked GF to clarify this and they declined to provide that level of detail. A follow-on plus process is planned that will add EUV usage at metal layers providing a shrink but requiring a redesign. GF has been using the EUV tool at CNSE for development, in their Malta Fab 8, GF has 1 EUV tool being installed, 1 being delivered later in December and 2 due in 2018.

2.0 Discussion

In this section I will compare some of the key characteristics of the processes.

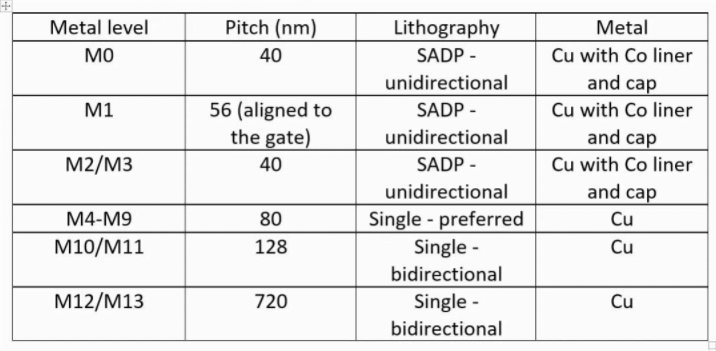

2.1 Fin shape 【鳍片形状】

when Intel first introduced FinFETs at 22nm, the bottom of the fin was significantly wider than the top. At the time there was a lot written about the impact of this shape on performance. An ideal fin is rectangular with some rounding of the upper corners to prevent hot spots. If the width of the fin varies from top to bottom the different widths will result in different electrical behavior. I have heard that if you measured Intel’s early 22nm fins they actually looked like two transistors. Figure 1 compares Intel’s 10nm fin on the left to GF’s 7nm fin on the right. Fins are much more rectangular today than the were back in 2011 when Intel introduced their 22nm process. The GF process appears to have more rectangular fins than the Intel process.

Figure 1. Intel fin shape (left) and GF fin shape (right).

2.2 Work Function metals for threshold adjust

Intel provides 4 or 6 work function metals for 2 or 3 threshold voltages and GF provides 8 work function metals for 4 threshold voltages. The number of threshold voltages likely represents the different process targets. GF is targeting foundry users that expect a high number of threshold voltages for low power applications and Intel is likely targeting high performance microprocessor applications. The use of work function metals to set threshold voltages allows the channels to be undoped, this provides two advantages. First, undoped channels have higher carrier mobility and therefore higher performance. Undoped channels also eliminate random dopant fluctuation (RDF) and make threshold voltage distributions tighter.

2.3 Cobalt versus copper interconnect【钴 vs 铜互联】

A lot has been made about Intel having cobalt and GF not having cobalt since these papers were presented. It has even been incorrectly reported that GF doesn’t have cobalt on their process. GF has cobalt filled contacts but doesn’t use cobalt for interconnect layers (although you can use the cobalt trench contact for local interconnect). Intel has cobalt filled contacts, 2 cobalt interconnect layers and 1 layer of cobalt filled vias.

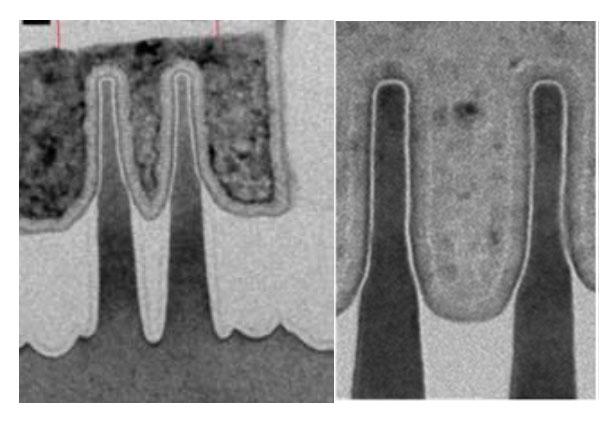

The resistance of an interconnect line is illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2. Interconnect line resistance.

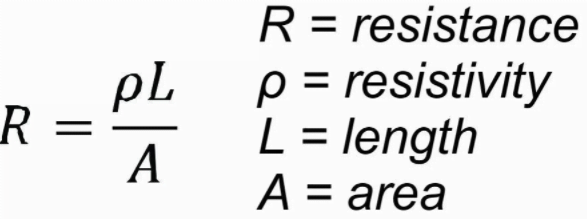

The formula for resistance is presented in figure 3.

Copper replaced aluminum for interconnect use around the 130nm node because copper has a bulk resistivity of 1.664 microohm-cm and aluminum has a bulk resistivity of 2.733 microohm-cm. Cobalt has a bulk resistivity of 6.247 microohm-cm and you wouldn’t think that it would be an attractive candidate to replace copper in interconnect applications, however, at very small dimensions the resistivity of copper increases due to electron scattering. Cobalt is much less susceptible to this effect than copper due to an electron mean free path roughly one third of coppers. Also, copper requires thick high-resistivity barrier layers that don’t scale down in thickness and at small dimensions become a significant percentage of the cross-sectional area of the interconnect. Cobalt has more forgiving barrier requirements and the net result is that at a small enough linewidth cobalt becomes a lower resistance interconnect. The specific linewidth where cobalt becomes a lower resistance interconnect solution depends on several factors but is right around the linewidths being utilized here. My belief is that Intel used cobalt because they have a 36nm MMP and it made sense for them to do so. GF published a paper on 7nm process development with IBM and Samsung at IEDM in 2016 and that process had 36nm MMP and used cobalt for one level of interconnect. My belief is that with a 40nm MMP in the GF 7nm process cobalt wasn’t needed and it is more expensive than copper, so GF didn’t use it. Cobalt also offers higher electromigration resistance than copper and GF did use cobalt liners and caps around their copper lines to meet their electromigration goals.

The bottom line is Intel used cobalt because it makes sense for their process and GF didn’t because it didn’t make sense for their process. As we move to foundry 5nm and below processes I do expect to see more cobalt use and eventually ruthenium.

【用不用钴不是技术问题,而是合不合理的问题。】

2.4 Density【制程密度】

When comparing process density there are many options in terms of metrics.

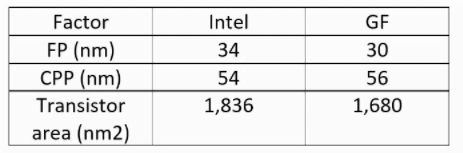

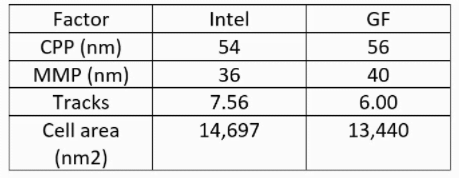

The size of a single transistor is the Fin Pitch (FP) multiplied by the Contacted Poly Pitch (CPP). The transistor sizes for the 2 processes are presented in table 3.

Table 3. Transistor size comparison.

By this metric GF’s aggressive FP leads to a smaller transistor size. The problem with transistor size as a metric is it doesn’t consider routing and isn’t reflective of actual design area.

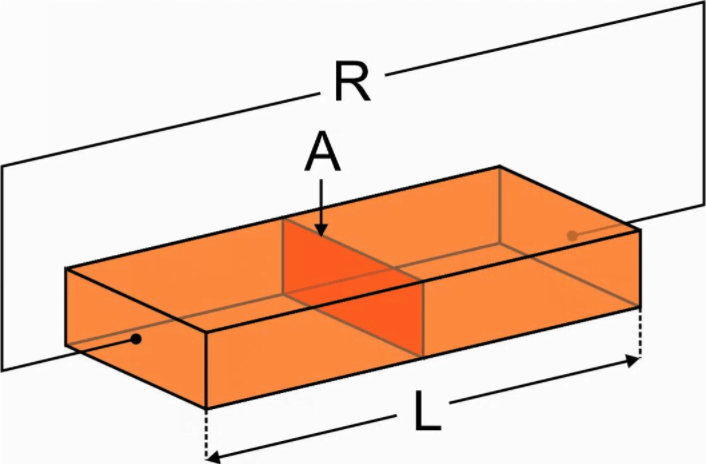

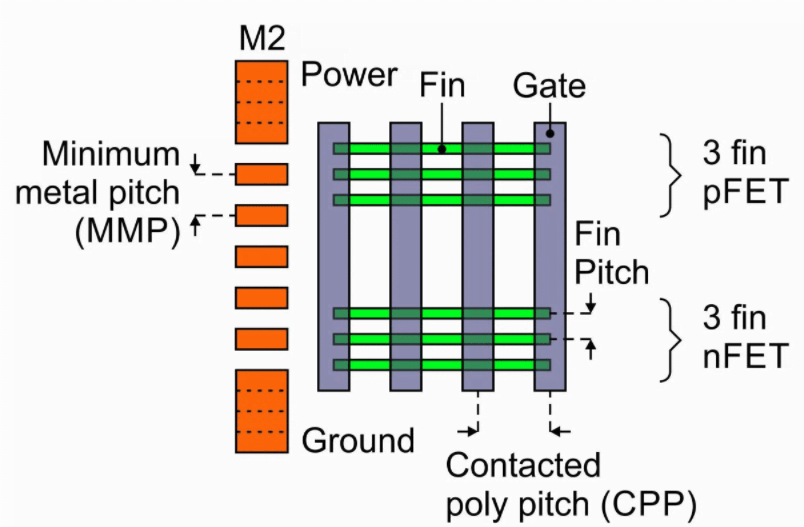

Actual logic design is done using standard cells so metrics describing standard cell size are more useful. Figure 4 illustrates a 7.5 track cell similar to Intel’s 7.56 track cell.

Figure 4. 7.5 track standard cell.【常说的7.5T】

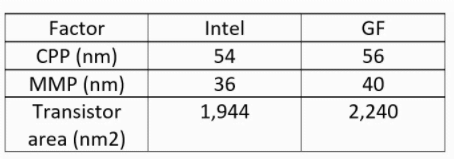

In process density comparisons from a few years ago it was common to use CPP x MMP as a cell size metric. Table 4 presents that calculation for the two processes.

Table 4. CPP x MMP comparison.

By this metric Intel would appear to have the smallest cell size. The problem with this metric is that in recent years Design Technology Co-Optimization (DTCO) has become an important practice in technology development and track heights have become another scaling nob. From figure 4 we can see that the actual cell size is Track Height x MMP x CPP. Table 5 presents this data for both processes.

Table 5. Standard cell sizes.

By this metric GF has the smallest cell size. However, in the Intel section we discussed how Intel eliminated dummy gates at the cell edges and this enables tighter cell packaging.

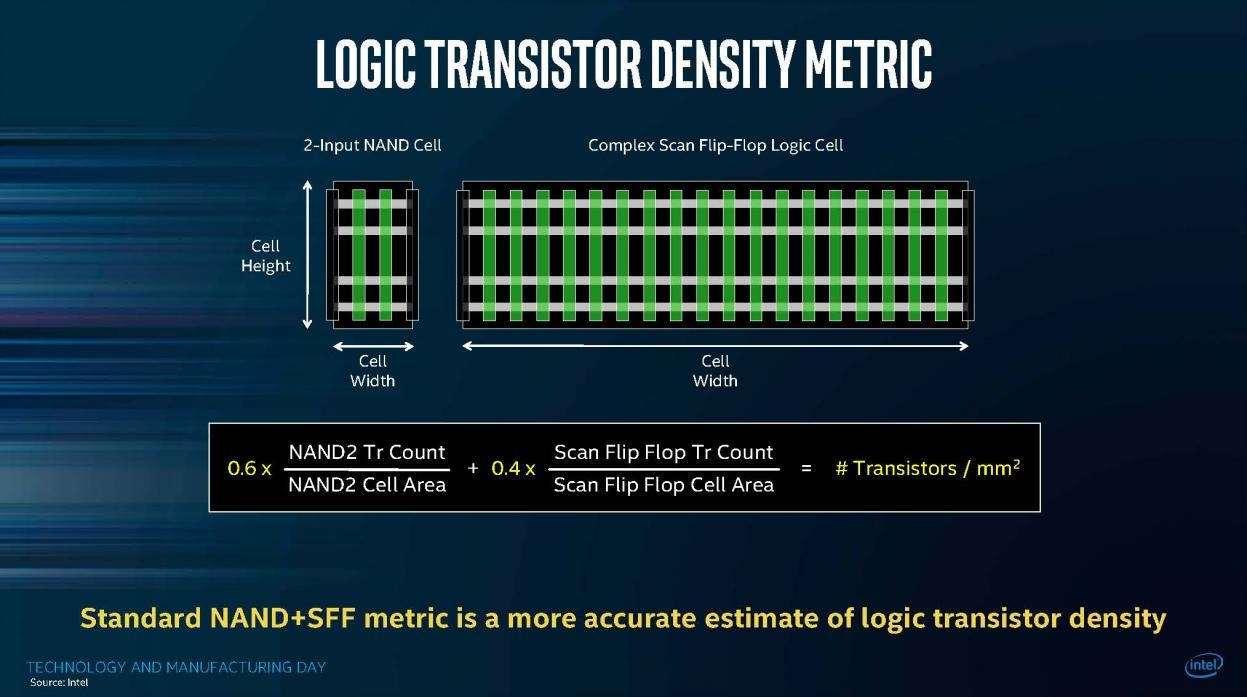

Intel has recently tried to reintroduce a metric to the industry based on the area of a NAND cell weighted at 60% + the area of a scan flip flop weighted at 40%. Figure 5 presents the Intel method, this was also shown and discussed in the Intel paper.

Figure 5. Intel density metric.

The claim is these cells and weightings are typical of logic designs. Intel has disclosed that by this metric their 7nm process archives 100.8 million transistors per millimeter squared. There are two problems with this metric, the first is Intel is the only company reporting based on this metric, the second is the foundries contend this metric doesn’t captures the subtleties of routing. In spite of these issues I have attempted to make my own estimates based on this. For Intel I get 103 million transistors per millimeter squared versus the 100.8 they report and for GF I get 90.5 million transistors per millimeter squared. The big difference here is that GF requires dummy gates at the edge of the cell and Intel doesn’t and that gives Intel a big advantage in the scan flip flop area.

High density SRAM cell size is 0.0269um2 for GF and 0.0312um2 for Intel so SRAM heavy designs will see an advantage with the GF process.

Ideally someone would design an ARM core in both processes and disclose how the size compares, baring that, after evaluating all of these metrics it appears these two processes offer similar density and the size of a design will depend on how the specifics of the design match up with the process characteristics.

2.5 Timing

The GF 7nm process is expected in the second half of 2018. The Intel 10nm is already late and I am hearing late 2018 and possibly even 2019 before it enters production. This presents a fascinating change in the semiconductor industry. Intel introduced 45nm, 32nm, 22nm and 14nm in 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2014 respectively. For many generations Intel was on a 2-year process introduction cadence, now they have gone to 3 years and 4+ years and while their scaling at 14nm was such that even at 3-years their yearly scaling pace was unchanged, they are now drifting off of that at 4+ year. It also begs the question of when Intel will introduce 7nm, are we now looking at 2022 or 2023?

In the mean time TSMC introduced 10nm in 2016/2017 and 7nm in 2017/2018 with 5nm due in 2019 and 3nm development underway. Samsung also introduced 10nm in 2017 with 8nm due 2017/2018, 7nm due 2018/2019, 6nm and 5nm due in 2019 and 4nm in 2020. GF is introducing 7nm in 2018 with a shrunk version due around 2019. GF hasn’t discussed 5nm yet but I would expect it this decade. With the foundry 7nm processes similar in density to Intel’s 10nm process and several foundry generations likely to come out by the time Intel introduces 7nm, I would expect a significant density advantage for the foundries over the next several years.

2.6 Performance

I wish I could offer a performance comparison between the processes but based on disclosures to-date I can’t. Intel is focused on microprocessor performance and GF and the other foundries are more focused on the mobile space and power for performance, beyond that I don’t have anything definitive to say on performance.

3.0 Conclusion

Comparing Intel’s 10nm process to GF’s 7nm process they are more similar than they are different. Since both companies are solving the same difficult physics problems this is in some ways not surprising.

The surprising part in my opinion is that GF at 14nm stumbled so badly they had to license it from Samsung. Now they have an internally developed 7nm process that matches up well with Intel’s latest 10nm process.

It is also surprising to me to see how far Intel has fallen from the process lead they had. First with HKMG by several years, first with FinFet by several year, I suppose they are still first to do cobalt interconnect but in terms of process density the foundries have caught them and appear poised to take a substantial lead over the next several years.

With Intel offering foundry processes and GF, Samung and TSMC all offering leading edge processes the industry now has four viable leading edge process options.

这时候就显现出AMD独占GF产能的优势来了,亲儿子终于养大了~

我认为台积电7nm的产能NV抢不过苹果,所以7nm N卡可能要延后,而A卡有可能会取得时间优势。

目前来看台积电 GF的7nmDUV进度相当,明年末拭目以待~

一度领先其他家1-2代,到了10/7nm这代突然就被追平了?所以intel遇到了什么?

@gartour:这方面Intel是无论如何都不会公布的

如果公布会出大事情…

CNL-Y据说会早点出

和初代14nm一样的套路,太差所以只能先做最鶸的-Y系

那代真正的高性能过了一年才出。

@剧毒术士马文:哇哇哇,好想知道里面的内幕

很多人的观点是Intel之所以不愿意快速推进10nm 是因为成本降不下来 苏妈前些天的演讲也提到 7nm成本是14nm的两倍

所以如果类似MCM的技术应该会帮助AMD取得一定优势

@NiceMing:不是。

CNL去年回炉你觉得是为什么

Intel 10nm不能推是因为真的很烂。成本和良率是另一码事。

一直闭口不敢谈10nm的进度,之前拿个Hyperscaling来糊弄糊弄

14+++++++++下去,其实就是原来步进/PDK更新,现在说成是一代进步

10nm如果能拿出来的话当然会拿出来

不然投资者和各类分析师会急的。

你说的那个我之前就提到了。那个是250mm2

@剧毒术士马文:苏妈说的每平方毫米成本两倍仅针对250mm2么?

这意思更大还可能没那么高成本?

比如500mm2

@wangbaisen1990:越大成本只会越高。

成本两倍综合了良率的。

@剧毒术士马文:哦哦,但是反过来如果要达到同样性能,或许会更便宜?毕竟密度也上去了

或者同样价格性能更好

几乎可以肯定navi会有一款以上使用mcm的产品,不知道是HPC专用还是游戏卡。只求redeon团队能在架构上下下功夫,不要只靠制程打架

@在amd看大门:以deep leaning为主 HPC交给vega20

马文

GF7nm和intel10nm差不多

都好于台积电10NM吧

这样看明年如果能按计划下半年正式量产

AU A卡算是获得了制程优势?

@wangbaisen1990:但是Intel 10nm跳票太久

官方说明年底

实际 拭目以待

@剧毒术士马文:嗯,以前一直有人说intel0nm是最好的

甚至好于gf7nm

这么看,真心不像

你们是文盲吧

怎么看都是GF的更有优势

@台湾佬:GF是给的FP低很多

总的来看这两个工艺是很接近的。

gf7nm仅仅密度上和intel10差不多 看来又是杯具

英特尔的肯定要好于格罗的。。吧?

@zd:还真不一定

10nm坑了太久

意思就是7nm的基本上就追上来了吧。。。

不过最后做出来东西差多少另说。

话说拿ryzen做文件存储服务器,有没有啥推荐的板子。

我看老外的homelab都几乎没am4的方案,tr的方案都太贵了。

结果一帮人还是绕着1230转。

350的插槽不够用,370的主板又贵又只给一堆一倍大的pcie口。

@nyanyan:然而这里GF7nm对比的是英特尔初代10nm 并不是10nm+

@CCTV:gf7nm也有几代……

@CCTV:CNL的10nm没计划

ICL的10nm+有消息

按照惯例10nm+应该会放宽一些

而且GF的7nm也有好几代

@剧毒术士马文:但是也不清楚zen2能不能跳过初代7nm 直接上7nmLP啊

@CCTV:7LP是平台

有不同工艺可以选择。

一般说的初代,指的是DUV吧

GF只在部分层用EUV可以减少mask数量,部署也能很快,但相应的不会带来芯片面积的减小

@nyanyan:7nm的确追上来了,按计划进度还比Intel要快。

目前只能预估一下密度,性能无法知晓。

NAS有QNAP的

买板子就不清楚了…

比较好奇intel又一次嘅发热密度=.-

@Vega 128:vega128打算上天么……

@wangbaisen1990:Rage128很精彩,期待Vega128会不会更精彩=v=

@Vega 128:噗绚丽核弹么

@Vega 128:这两家的工艺实际差不多

@剧毒术士马文:目前看是类似的,但是从后发优势来看,intel成本-性能问题导致回炉?